Imagine the frustration of searching for a misplaced item, like your house keys or wallet, before leaving for a night out. Now, picture a FedEx or Amazon delivery driver halfway through a tight morning route, struggling to locate a parcel due by 9 a.m. while parked right outside the customer’s address.

These misloads — where shipments are accidentally loaded onto the wrong delivery route or vehicle — not only cause stress and lost time for the delivery driver but also result in significant negative economic and environmental impacts. Misloads can also lead to customer dissatisfaction, erode trust in the delivery company, and necessitate additional vehicle travel miles to rectify the mistake. Despite this, little is known about the frequency of human errors in last-mile delivery and how they affect the overall supply chain. In this post, we define the concept of misloading and unpack some of these questions to better understand its implications and identify potential solutions.

What is misloading?

Misloading is generally considered an error in the Load Planning Problem (LPP). An LPP is a discrete optimization problem that considers a logistic network structure (set of nodes, or logistics terminals, and links, routes connecting terminals served by a given fleet of trucks) and the demand for freight (quantity, origin, and destination). The objective is to determine the optimal sequence of terminals that a load of freight should traverse to minimize handling costs and maintain a specified level of service. The outcome of an LPP is a “load plan,” which details a unique strategy to handle each shipment at every point in the system (Powell & Sheffi, 1983).

A shipment misload is a deviation from the load plan, which could occur due to intentional or unintentional actions. For example, during a ridealong I performed on a parcel delivery route in downtown Seattle (Dalla Chiara et al., 2020), the driver chose to deliver a bulky carpet earlier in the morning instead of the afternoon ahead of schedule in the morning rather than the afternoon, in order to create space inside the vehicle to safely and efficiently move around and retrieve packages from the shelves. Such intended deviation from the load plan improved the efficiency of the overall route. Conversely, unintended misloads often occur due to human errors (a shipment is misplaced on the wrong vehicle or route) or machine errors (a shipment is incorrectly labeled).

Frequency of misloaded packages

Misloading is often reported as a misloading rate (or its corresponding order accuracy rate) calculated by dividing the number of misloads by the total number of deliveries during a given time period.

The misload rate varies across industry sector, leg of the supply chain (whether hub-to-hub or preload), and even geographical location of logistics facilities. In the fast-moving goods sector, hub-to-hub misloads rate are reported to range from 0.01% to 0.1%, while preload misload rates have been reported between 0.1% and 0.3%.

While this may seem relatively small, misloading occurs daily due to the vast scale of delivery operations. For example, with a 0.2% misload rate, approximately one in 500 parcels is misloaded. Considering that a typical parcel delivery van handles around 250 packages per route, on average, every two vehicles would contain one misloaded package. Even with a lower misload rate of 0.1% (one in 1,000 packages), there would still be one misloaded package for every four delivery vehicles. In Seattle, where approximately 900 parcel delivery vehicles enter the greater downtown area daily (Giron-Valderrama & Goodchild, 2020), this equates to more than 200 misloaded packages every day. These figures highlight the frequency of misloading incidents despite their seemingly low percentage, and underscore the impact on operational efficiency and customer service.

We note that the misload rate increases the closer we get to the last mile of a delivery journey in the fast-moving consumer goods sector. From the data above, the misload rate quadrupled from the hub-to-hub to the last-mile segment (from 0.05% to 0.2%). This reflects increased manual labor, reduced automation, and increased complexity in handling smaller, non-standard parcels.

Quantifying the impact of misloading

Quantifying the economic and environmental loss of a misloaded package involves first understanding how drivers respond to these errors.

A preload misload is typically identified when a driver has either a missing package they are supposed to deliver or an additional package that does not belong on their assigned route. What happens next will depend on procedures implemented by the facility and other operational factors. In the case of a missing package deemed “critical,” the driver would typically alert nearby routes where the misloaded package is likely to have been placed). The driver might meet the other driver halfway, or the other driver may make the additional delivery. A “non-critical” package may be returned to the facility and rescheduled for delivery the following day. In either case, misloads result in additional miles traveled and the loss of driver time.

Quantifying the negative impacts of misloading is a difficult task. Transportation science often uses simulation tools to test different scenarios that are difficult to measure empirically by generating mathematical models. In this case, a misloading simulator takes as input the existing delivery demand and misload rate, calculates the optimal load plan, and outputs the total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and total route time under scenarios both with and without misloads. By running simulations with varying parameters (different demands and misload rates), the misload simulator can provide a sufficiently precise estimate of how the misloads affects route performance.

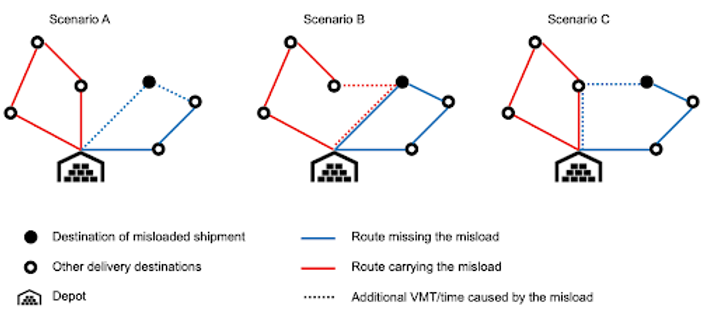

According to the previous section, misloading can cause three possible scenarios, depicted in the figure below. In all three scenarios, we identified two routes — the red route carrying the misloaded shipment, the blue route missing the misloaded shipment — and the full node representing the final destination of the misloaded shipment.

- Scenario A simulates the case of a misloaded non-critical package; in this scenario, the impact of misload is the additional VMT and time the driver spends on the blue route to reach the customer without being able to complete the delivery, as the shipment was misloaded on the vehicle carrying out the red route.

- Scenario B simulates the case of a misloaded critical package, where the driver of the red route is required to spend extra time and VMT to make an additional delivery.

- Scenario C simulates the case of a misloaded critical package, in which the driver of the blue route needs to spend additional time and VMT to meet the driver on the red route and retrieve the misloaded package.

The shape and length of delivery routes are extremely heterogeneous and vary among carriers, business sectors, and contexts. For instance, if we consider the case of a typical parcel delivery carrier delivering in downtown Seattle, a route averages 7.2 miles, with 24 stops, and an average distance of 0.3 miles per stop. A beverage company delivering in downtown Seattle typically has a 15-mile route with 11 stops and an average of 1.4 miles per stop (Dalla Chiara et al., 2021). Considering the simplest scenario to simulate (scenario A) and assuming the above-discussed misload rate of one misloaded shipment every two routes, a single misload would result in an additional 0.6 miles of travel, representing 4% of the total VMT. In the case of the beverage distributor, a single misload would leads to an additional 2.8 miles traveled, constituting 9% of total VMT.

Addressing misloading

Despite their statistical infrequency, misloads occur daily, affecting delivery times, increasing VMT, and eroding customer trust. Delivery companies strive to meet and exceed their misload target rates, but often struggle to identify effective solutions.

Addressing misloads involves a multifaceted approach that combines improved training and the adoption of advanced technologies. Developing clear procedures and providing training for drivers and preloaders can reduce human errors in labeling, sorting, scanning, and loading, as well as in detecting and correcting misloads. The Service Awareness Label Training (SALT) practice helps improve error detection. SALT involves placing fake misloaded packages in the system to assess employees’ ability to identify them.

Recent advancements in tracking technologies are creating new opportunities for delivery companies to reduce misloading. Since the introduction of scanning (the first item marked with a Universal Product Code was scanned in 1974 in a supermarket in Troy, OH, Weightman, 2015), most parcels are now scanned at key checkpoints, reducing human errors, generating a wealth of data that can be used to optimize the supply chain, and providing customers with real-time location and status information about their parcels.

Radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology, which allows multiple simultaneous scans, has allowed for substantial efficiency gains throughout the supply chain (Fan et al., 2015), enabling seamless tracking and reducing manual effort. While cost has historically been a major obstacle to full deployment (Bottani and Rizzi, 2008), 2022 seemed to be a tipping point in RFID implementation at scale (Swedberg, 2022). For instance, UPS launched a smart package initiative starting in 2022, deploying an RFID-based system through its facilities (Garland, 2022). The system involves placing RFID scanners on wearable devices and on delivery vehicle rear doors to automate preloading and eliminate manual scanning — and, therefore, the likelihood of misloads. Also beginning in September 2022, global retailer Walmart mandated that suppliers across several departments include RFID tags on all products shipped to its warehouses.

What’s next?

While the impact of misloading has been viewed mostly from a customer service perspective, its broader economic and environmental impacts are often overlooked. Implementing technologies like RFID can reduce misload rates, yet companies must weigh the cost and benefits of such investments. Quantifying the benefits of reducing misloads, such as decreasing VMT, lowering vehicle emissions, and improving drivers’ efficiency (among other potential efficiencies, for instance, Brewster, 2024) is important to guide companies in making informed decisions and optimize strategies.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge IMPINJ for their technical and financial support and the experts and practitioners who provided content for this article.

References

-

Powell, W.B., and Sheffi, Y. (1983) The load planning problem of motor carriers: problem description and proposed solution approach, Transportation Research Part A, Vol. 17A, No. 6, pages 471-480. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/019126078390167X

-

Dalla Chiara, G., Krutein, K. F., Ranjbari A., and Goodchild, A. (2021). Understanding Urban Commercial Vehicle Driver Behaviors and Decision Making. Transportation Research Record, 2675(9), 608-619. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211003575

-

Giron-Valderrama & Goodchild (2020). Characterization of Seattle’s Commercial Traffic Patterns: A Greater Downtown Area and Ballard/Interbay Vehicle Count and Evaluation, Urban Freight Lab, University of Washington. https://urbanfreightlab.com/publications/characterization-of-seattles-commercial-traffic-patterns-a-greater-downtown-area-and-ballard-interbay-vehicle-count-and-evaluation

-

Weightman, G. (2015). The History of the Bar Code, The Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/history-bar-code-180956704

-

Fan, T., Tao, F., Deng, S., and Li, S. (2015) Impact of RFID technology on supply chain decisions with inventory inaccuracies, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 159, pages 117-125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.10.004

-

Bottani E., Rizzi, A. (2008) Economical assessment of the impact of RFID technology and EPC system on the fast-moving consumer goods supply chain, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 112, Issue 2, pages 548-569, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.05.007

-

Swedberg, C. (2022) Walmart Recommits to RFID, The RFID Journal, https://www.rfidjournal.com/walmart-re-commits-to-rfid-with-supplier-mandates

-

Garland, M. (2022) UPS to deploy RFIDs through 100 facilities this year, Supply Chain Dive, supplychaindive.com/news/ups-smart-package-initiative-facilities-2022-rfid/623017

-

Brewster, M. (2024) Combat Carbon: RAIN RFID’s Effect on Supply Chain Sustainability, IMPINJ Insights, impinj.com/library/blog/rain-rfids-effect-on-supply-chain-sustainability