By David Zipper

If you so much as glanced at the IPCC’s terrifying new report on climate change, you know its message: To have a chance of avoiding environmental collapse, we need to adopt every emissions reduction tool available, immediately.

That warning has fallen on generally receptive ears in America’s left-leaning cities. Officials in many urban areas are already dealing directly with the impacts of extreme weather, and few of them have questioned the urgency of out predicament. Many have issued passionate calls for action. Mayors of New York, Seattle, Phoenix, and Portland are among the many who have issued net-zero pledges.

So it seems odd that one very obvious climate-fighting implement — the electric cargo bicycle — remains such a rare sight in American cities.

Heavy-duty bikes and trikes equipped with batteries for extra pedal power could replace many of the delivery vehicles that haul packages around cities. A recent study of London found that cargo bikes could reduce emissions from package delivery by one-third compared with electric vans, and by 90% compared with diesel ones.

Cargo bikes offer other substantial benefits, too. Unlike delivery vans, they seldom obstruct traffic lanes, cycle paths or crosswalks when idle. And they don’t worsen street congestion by circling the block in search of a place to unload, which can consume up to 28% of van drivers’ time, according to one Seattle study. With cities struggling to cope with a traffic-snarling surge in online purchases, cargo bikes offer a way to address increasingly overloaded curbs and streets.

Logistics companies could themselves come out ahead with a shift toward cargo bikes. The London study found that cargo bikes delivered an average of seven packages per hour, compared with four for a van. (The comparative ease of parking a bike had a lot to do with that.)

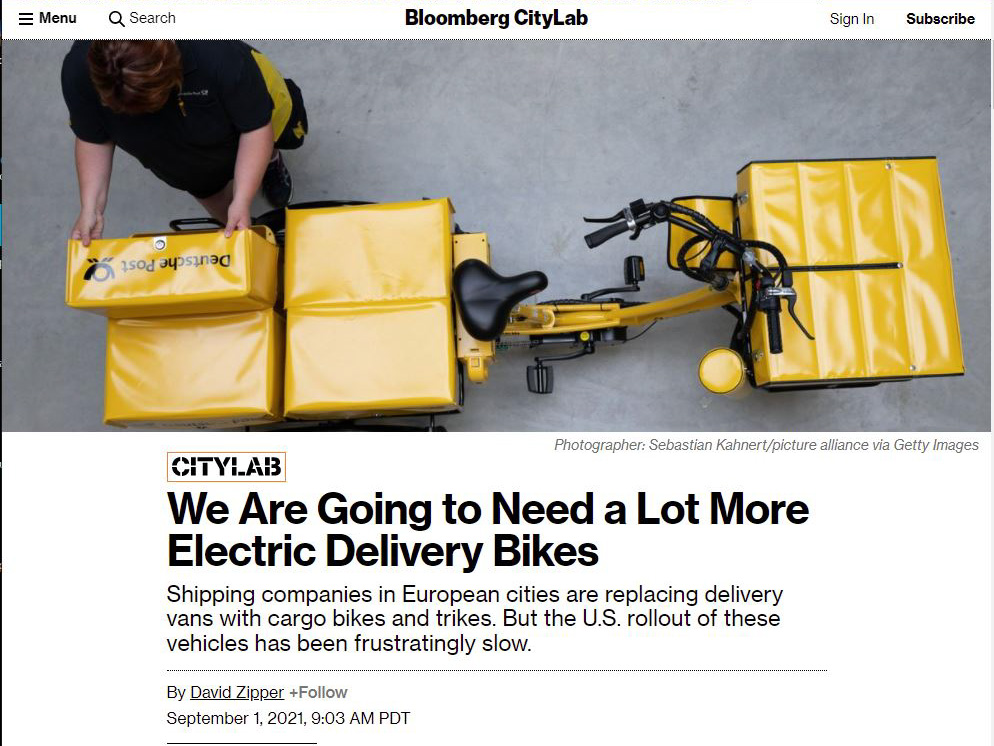

Globally, the cargo bike market is expanding quickly, with one market research group projecting $900 million in worldwide sales this year, 43% of which would come from cargo bikes sold to businesses. Europe has been a particular hotbed. In Germany, DHL/Deutsche Post now manages a fleet of nearly 17,000 cargo bikes and trikes, with another 5,000 on order. “The change in the last five years here has been extraordinary,” says Kevin Mayne, CEO of Cycling Industries Europe, an industry group. “Most of the cargo bike manufacturers now have two divisions: one for consumers and one for businesses. If anything, growth in the business-to-business side is bigger.”

But in the U.S., DHL/Deutsche Post has made only tentative steps to introduce cargo bike delivery. According to a DHL spokesperson, the company has launched one American pilot: a Miami deployment involving just four vehicles. That is still more than the single cargo bike that UPS unveiled in Portland at a public event in 2019. (UPS declined to comment.) Amazon, for its part, has struggled to scale its two-year-old pilot involving three Whole Foods stores in New York City, which a spokesperson says includes around 200 vehicles. Meanwhile the e-commerce company has placed an order for 100,000 electric delivery vans from Rivian.

Why hasn’t the European wave of cargo bike delivery swept across the Atlantic? It’s a complex question, but one conclusion seems apparent: If American cities want cargo bikes to play a bigger role with package delivery, simply asking shippers for help won’t do it. They’re going to need to restrict delivery van access.

To understand why, consider Boston. By American standards, New England’s biggest city is unusually dense, with almost 14,000 people per square mile (more than Marseille). That should make it fertile ground for cargo bike delivery, which is more efficient in places where pickup and drop-off locations are clustered together. And, like most European cities, it’s got a pre-automotive-era street layout (plus some of the nation’s worst traffic congestion).

Why hasn’t the European wave of cargo bike delivery swept across the Atlantic? It’s a complex question, but one conclusion seems apparent: If American cities want cargo bikes to play a bigger role with package delivery, simply asking shippers for help won’t do it. They’re going to need to restrict delivery van access.

To understand why, consider Boston. By American standards, New England’s biggest city is unusually dense, with almost 14,000 people per square mile (more than Marseille). That should make it fertile ground for cargo bike delivery, which is more efficient in places where pickup and drop-off locations are clustered together. And, like most European cities, it’s got a pre-automotive-era street layout (plus some of the nation’s worst traffic congestion).

Boston is also led by local officials eager to support cargo bike delivery. “In 2017, we committed to be carbon neutral by 2050, and we knew 29% of our emissions come from transportation,” says Kris Carter, the co-chair of the Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics. “We thought, let’s get a lay of the land for cargo bikes through a Request for Information [a formal invitation for external groups to share ideas with the city] that would say ‘we are interested in this technology and vehicle type, and we want your ideas for how to accomplish our goals.’”

Carter and his colleagues saw cargo bikes offering a ripe opportunity for public-private partnerships, giving shippers a chance to reduce traffic tickets accrued from illegally parked delivery vans. (UPS alone pays the city around $800,000 annually in fines, Carter says.)

Boston issued a cargo bike RFI in August 2020. Carter says that the city received 19 responses from bike manufacturers and data management groups, but none from global logistics companies. “It isn’t clear there’s a lot of interest in doing cargo bike delivery in Boston,” he says, with just a touch of frustration. “We need them to come to the table, because we don’t run a logistics service. They do.”

Giacomo Dalla Chiara, a research associate at the University of Washington’s Supply Chain Transportation and Logistics Center, sees numerous obstacles blocking the adoption of cargo bikes in the United States, even in places like Boston that seem well-suited for them. One is the general lack of cargo-bike-friendly infrastructure. Dalla Chiara says that more extensive networks of protected bike lanes could facilitate cargo bike delivery. In a forthcoming research paper, he and colleagues examined a recent cargo bike pilot in Seattle and found that the delivery cyclists rode on the sidewalk around 40% of the time.

A DHL spokesperson echoed that concern, saying that the groundwork for Europe’s embrace of cargo bikes was laid by “countries that have invested significantly and for a long period of time in the engineering and construction of bike-friendly roadways.” Europe is now so far ahead of the U.S. on cargo bikes that the company would have to ship equipment from overseas to do an American deployment, adding “significant costs associated with transportation and import,” according to the spokesperson.

The other pressing infrastructural issue is the lack of U.S. “microhubs” — physical locations where shippers can consolidate vehicles and parcels. “You need charging infrastructure and overnight storage for the bike,” Dalla Chiara says, “as well as space for a van to deliver packages to the microhub in the morning.” Inertia favoring the status quo of van delivery also presents a challenge. “The big shippers are running software that isn’t designed for cargo bikes,” Dalla Chiara says. “It doesn’t take into account the presence of bike lanes or the steepness of the road.”

Finally, some U.S. legal barriers to cargo bikes would need to be lifted. New York, for example, bans cargo trikes that are wider than 36 inches wide, effectively outlawing many of the larger heavy-duty models. The state’s legislature is currently considering a bill that would allow cargo bikes to extend up to 55 inches.

One factor that Dalla Chiara does not think plays a central role in cargo bike adoption is the fact that logistics companies receive so many fines from delivery vans parked illegally — that’s just a manageable cost of doing business. (Example: UPS’s $23 million in fines paid to New York City in 2019 equated to 0.04% of the company’s annual revenue). “The companies are just ignoring them,” Dalla Chiara says.

Mayne acknowledges that comparatively sprawling American cities present added challenges for cargo bike delivery. “Whether you like it or not, we Europeans have the advantage of density,” he says. But he doesn’t buy shippers’ claims that they can’t deploy cargo bikes unless cities help them first secure ample loading space. “The argument is basically bullsh*t,” he says. “It just means you don’t want to do it.”

The simple solution: “Just take one floor of a parking lot and make it a microhub,” Mayne says, pointing to a recent project in Dublin. Public support has helped microhubs open in other European cities as well, including Prague and Berlin.

In fact, cargo bikes are now so widespread in some European cities that they are creating new problems. Shippers are shifting toward wider bike models, which can carry more parcels but also crowd bike lanes, Mayne says. “Once you have a bike that’s a pallet wide — 1.2 meters — you really need a bike lane that’s 1.5 meters, or two meters if there is another cargo bike going the other way,” he says. “There are not many places where two-meter bike lanes are standard.”

For now, at least, that’s a problem that American cities like Boston would love to have. I asked Mayne what he would suggest to a city official on the other side of the Atlantic who wonders how she could tap the potential of cargo bikes to achieve her city’s goals around sustainability and mode shift. His answer: Think first and foremost about motor vehicle access restrictions.

“It’s not about the cargo bikes; it’s about the delivery vans,” Mayne says. “The cargo bikes will come when there is an imperative for the vans not to.”